The Bible offers a model for spirituality (union with God) through the sanctuary covenant structure that offers a compelling and authentic alternative to other models of Christian spirituality.

Silvia Canale Bacchiocchi

More than ever, we are living at a time of increasing fascination with the concept of spirituality, so much so that the “spirituality phenomenon” has come to define our era.1 Some see this as the result of the psychoanalytic movement begun by Freud, or disappointment with the Enlightenment’s faith in progress (a failure largely caused by 20th-century wars). Others see it as resulting from the futility of modern existence or the teachings of Vatican II. Whatever the cause, it appears that many—whether religious or atheist—are seeking to connect with God or a higher power. Spirituality centers have mushroomed across the globe, and countless books are devoted to the topic. Yet are all spiritualities equal? Do all spiritualities connect us with God? What does the Bible teach?

There are many spiritualities in the world, but Scripture affirms only one. This biblical model for spirituality (union with God through Christ) is depicted in the sanctuary‑covenant structure, which offers a spiritually compelling and biblically authentic alternative to other models of Christian spirituality.

Historical Background

Christian spirituality originally centered on restoring the image of God in humanity. In early Christianity, the apostles spoke the need to “walk in the Spirit” (Gal. 5:16).2 which implied restoring the image of God through the cognitive renewal of the human mind—that is, impressing the wisdom of God on the minds and hearts of humans, and then living according to this new and ever‑growing knowledge of God and His will (Rom. 7:22; 12:2; 2 Cor. 10:5). Paul warned believers to not be conformed to the world’s pattern of thinking, but instead to be transformed by the renewal of their minds (“mind,” “understanding,” “reason”), which is the Christian’s reasonable (“rational”) service, so they might prove the good and perfect will of God (Rom. 12:1, 2).

Even during Paul’s day, Neoplatonic philosophy presented a challenge to the church. This method was based on a mystical approach to spirituality, which sought to surpass reason and the spatiotemporal realm to experience the presence of the divine, presumed to exist beyond space and time. Paul repeatedly warned against these Gnostic heresies attempting to infiltrate the church (1 Tim. 6:20, 21; Col. 2:8; 1 Cor. 1:18–31). Among other things, Paul denounced the Neoplatonic philosophy present in the over‑realized eschatology of the church, in which some were teaching that Jesus had already returned and was present to believers in a mystical way (2 Thess. 2:1–4). And it was not long after the first generation of Christians passed away that this mystical method began to replace the biblical‑cognitive approach to spirituality.

Christians were no longer exhorted to study Scripture as the only means to understand the mind of God and become conformed to His image; instead, a worldly sophia or philosophy of spirituality began to emerge in Christianity. Now it was assumed that Christians could achieve a mystical connection between their presumably timeless (nonrational) soul and a presumably timeless God. And although selected texts of Scripture might be used, the typical method of experiencing Christ’s mystical presence centered on the eucharistic meal, which was thought to convey not only the bodily presence of Christ, but also salvation. This mystical method quickly overtook the cognitive‑biblical as the default approach to spiritual union with God. No longer was the second coming of Christ the focal point, as Christ was now believed to have returned mystically and was spiritually available to all enlightened believers through the Eucharist. Paul’s repeated warnings against adopting this mystical view of Christ’s parousia went unheeded by the church fathers. A mystical spirituality continued through the Middle Ages and the Reformation, and is very much prevalent today. The center of most models of Christian spirituality is no longer a daily conforming to the image of Christ as revealed in His Word, but, rather, on experiencing His mystical presence through rituals such as the Eucharist, music, art, or human rhetoric.

Spiritual Mysticism Concealed or Biblical Mystery Revealed?

If Scripture does not endorse spiritual mysticism, how did it gain a foothold in the church? For this, we should note that while the term mysticism is fairly recent, created in the 17th century and popularized around the 19th, the word mustērion, meaning “hidden” or “secret thing,” has been in use since the ancient Greeks. It was derived from another word, meaning “to close the eyes or lips,” and “initiate.”3 The connection between the two words likely arose from secret religious ceremonies in ancient Greece, which were witnessed only by the initiated who were made to swear they would not divulge what they had seen. Mystery was thus something revealed to a select few, but to the rest it remained hidden, esoteric, and impossible to know.

By the fifth century the Neoplatonist Pseudo‑Dionysius formally introduced mysticism into the church, coining the term mystical theology, which he related to symbols and rituals that go beyond a cognitive relation to God “to a real union with Him in the ‘truly mystic darkness of unknowing.’”4 Pseudo‑Dionysius believed that when Moses entered the cloud at the top of Mount Sinai, he broke from a rational understanding of God and “[entered] into the truly mysterious darkness of unknowing. . . . Here, being neither oneself nor someone else, one is supremely united to the completely unknown by an inactivity of all knowledge, and knows beyond the mind by knowing nothing.”5

Following Pseudo-Dionysius, many theologians interpreted God as unknowable by reason or history, misinterpreting texts that say God dwells in a thick cloud (Lev. 16:2; 2 Chron. 6:1; Ps. 97:2). However, rather than indicating His separation from history, these and similar texts reveal that the cloud was an indication of Christ’s guiding presence in Israelite history (1 Cor. 10:1, 2), particularly above the mercy seat in the Most Holy Place of the sanctuary, from which God revealed His will to the Israelite nation (Ex. 25:22; 33:9). The cloud of God’s presence did not mean He was shrouded in mystery, but the opposite—His desire to dwell among His people and speak with them, that they might fully know His will.

While the New Testament does not use the term mystical, we do see the related word mustērion (“mystery”), but again this is used to highlight God’s revelation. In other words, what was once unknown or hidden—God’s contingency plan to provide a way of salvation for humanity should they fall, a plan established from the foundation of the world (Eph. 1:4; Rev. 13:8)—God has been revealing since the fall of humanity. Paul proclaimed “the revelation of the mystery kept secret since the world began but now has been made manifest, and by the prophetic Scriptures has been made known to all nations, according to the commandment of the everlasting God, for obedience to the faith” (Rom. 16:25, 26, italics supplied).

Thus, “mystery” in Scripture is none other than the gospel—God’s plan to restore spiritual union with humanity—revealed in embryonic form to Adam and Eve (Gen. 3:15) and then made explicit by God’s self‑revelation to Moses and the Israelite nation through the Exodus sanctuary‑covenant structure, a revelation that the Israelites were to share with all nations (Ex. 19:6). After Moses, the prophets continued to reveal God’s wisdom/sophia, most notably Daniel in whose writings we find the only Old Testament parallel of mustērion in the Aramaic section of his book (Dan. 2:18, 19, 27–30, 47; 4:9). Daniel affirmed that “‘there is a God in heaven who reveals mysteries, and he has made known to King Nebuchadnezzar what will be in the latter days’” (Dan 2:26, ESV). Here we see that the prophecies of Daniel—which explain the historical development of the Great Controversy and center on God’s role through the sanctuary‑covenant—are grounded on the fact that God is the great Revelator. Daniel’s prophecies reveal the time of Christ’s baptism, crucifixion, and mediation in the heavenly sanctuary, particularly the investigative judgment begun in 1844. Christ then revealed Himself in the flesh to substantiate all that the prophets had spoken of Him, and after His ascension appeared to John on the island of Patmos to give a parallel yet deeper revelation of the mystery of salvation in the Book of Revelation.

So, it can be affirmed that “the secret things belong to the Lord our God, but those things which are revealed belong to us and to our children forever, that we may do all the words of this law” (Deut. 29:29). Because God is the Creator and we are mere creatures, we can never fully comprehend some truths, such as the nature of the Trinity or the full extent of His selfless love. But He has given us all the knowledge we need to love and obey Him by keeping His law, which is the transcript of His character.

Thus, Scripture denies a mystical theology of spirituality that requires us to go beyond reason and the spatiotemporal realm of history to experience God and instead clearly proclaims the once‑hidden will of God, progressively revealed through the acts of salvation history. Yet, despite the testimony of Scripture, mystical spirituality has continued to the present time. In the early 20th century, the Catholic Church replaced the centuries‑old use of mysticism and its alternate forms (such as “mystical union” and “mystical theology”) with spirituality and its various forms. So today when most theologians speak of spirituality, they are essentially still referring to the mysticism grounded on the philosophical origin of Platonic dualism which Pseudo‑Dionysius and other theologians propagated in early Christianity.

The Proper Ground for Spirituality: Biblical Philosophy

To understand how, despite the clear teachings of the Bible, theologians continue to insist on a mystical/timeless approach to spirituality, it is helpful to understand the role of philosophical origins. There are two basic ways to view philosophy: (1) the point of departure or grounding belief about reality that orients the philosophical pursuit [philosophical origins]; or (2) the teachings and maxims resulting from it. For example, Socrates’ optimistic soliloquy on the afterlife, given at his trial, is a teaching or belief that stemmed from his philosophical point of departure: the immortality of the soul. Likewise, the teaching of Hinduism against eating meat originated not from dietary concerns but from Hinduism’s belief in reincarnation, which is grounded on the immortality of the soul.

Every teaching or belief begins with grounding assumptions—known or unconscious—regarding ultimate reality. Every single person, whether aware of it or not, has these basic assumptions about reality. This is simply the structure of human reason. These basic assumptions may be grounded in the study of Scripture, other books, or simply absorbed through one’s culture. The quest to define these basic presuppositions is philosophical because it explores the nature of reality at its core. The basic question explored by general ontology is What is real? In regional ontology, theology studies the nature and revelation of God, anthropology looks at the origin and nature of nature of human beings, and cosmology studies the origin and nature of the cosmos. Epistemology then explores human knowledge in relation to revelation-inspiration, hermeneutics, and method. Finally, metaphysics explores the way all of these parts unite in a coherent totality or whole.

Questions regarding origins and epistemology can be answered in more than one way; mythology, science, and different religions offer unique answers based on how they answer the most grounding ontological question—What is real? The answer given by Parmenides and Plato (whom Western civilization has followed) is that reality or being is timeless, static, and immaterial. Plato’s two‑world, or dualistic, cosmology claims the “real world” exists outside of time and thus cannot be known in our spatio-temporal world. Scripture, however, presents a diametrically different picture of ultimate reality that is established by God’s self‑revelation as an analogically temporal Being who was dynamically active first in creation and now in redemption history. God’s Being then defines reality and all the other macro‑hermeneutical presuppositions: cosmology, anthropology, epistemology, and metaphysics. However, God’s explanations in Scripture do not appear in a tidy systematic outline, but through a sweeping historical narrative that engages other literary genres including prophecy, law, poetry, genealogy, and wisdom literature.

Yet instead of grappling to discover the foundations of God’s philosophy embedded in the biblical narrative, most theologians have uncritically accepted Greek philosophy’s grounding interpretation of being (ontology) as timeless and interpreted Scripture through that presupposition. This single presupposition, then, essentially discredits anything that happens in the historical flow of time (for instance, Christ’s sacrificial death becomes an allegory of God’s timeless love, but not a real event necessary for the salvation of humanity). To these theologians the text of Scripture is not the clear and authoritative Word of God but simply a temporal wrapping that must, eventually, be discarded to capture the core of real truth presumed to exist beyond the simple historical narrative.

One example: Augustine was perplexed by the cognitive dissonance he saw between timeless philosophy and Scripture’s affirmation that God exists in spatiotemporal history. In his Confessions, he wrestled to reconcile the plain word of Scripture with his Neoplatonic philosophy, but ultimately the latter won out. Augustine clearly stated that God speaking in Scripture is not real (does not convey reality). Hence, he dismissed divine revelation in favor of a voice he heard, presumably God’s voice, speaking in his “inner ear.” This inner voice confirmed to him that Scripture must be interpreted through the presupposition of timelessness. As noted in the diagram below, this single decision—which classical, Protestant, and modern theology has embraced—automatically dictates the rest of the grounding or macro‑hermeneutical categories, including God’s nature (theology proper), human nature (anthropology), the world (cosmology), knowledge (epistemology, including the study of hermeneutics, revelation, inspiration, and theological method), and the relation of the parts to the whole (metaphysics). In other words, once being is defined as timeless, the rest of the macro‑hermeneutical categories follow suit in domino progression, all adhering to a timeless/spiritual nature. These, in turn, influence the meso‑hermeneutical (doctrinal) and micro‑hermeneutical (exegetical) outcomes in theology.

Figure 1

Thus, while most theologians generally use Scripture to support their conclusions, many upholding sola Scriptura in principle, in practice their point of departure or philosophical origin is the traditional ontological presupposition that Being/reality is timeless. So, when they use Scripture, they do so selectively and interpret the favored texts through underlying philosophical presuppositions that tend to negate the very claims of the biblical text. This distorts their perception of the God of Scripture and the resulting doctrines that describe Him. And this is acceptable to them because, in the end, their goal is to reach a mystical union that lies beyond cognition in general and Scripture in particular.

In contrast to this approach are the sola and tota Scriptura principles. Because all Scripture has been inspired by God (2 Tim. 3:16; 2 Peter 1:21) the claims of Scripture must be seriously considered in their totality (tota Scriptura). Second, this study assumes that Scripture presents a coherent philosophy, grounded on the basic principles of reason mentioned above—being, theology, anthropology, cosmology, epistemology and metaphysics. (Metaphysics is also referred to as the principle of articulation.) In this way, Scripture offers a philosophical system of understanding ultimate reality (the macro‑hermeneutical realm) that is as valid and rational as the traditional Platonic system espoused by most theologians.

Christ Reveals the Philosophical System of Biblical Theology

Although human philosophy uses human teachings (primarily based on the timeless interpretation of being/reality advanced by Parmenides and Plato) to define who God is and how He can be experienced, in Christ’s philosophical system, God Himself defines the parameters by which He is to be known. In other words, God defines being/reality not as timeless, but as deeply historical and spatiotemporal. An introductory overview suggests three elements of Christ’s biblical philosophy:

1. God’s Word is the epistemological foundation. While most theologies are constructed using Scripture and human teaching—whether from philosophy, science, or experience—Christ establishes the Word of God as the sole foundation for knowing Him. In Matthew 4:4, Jesus exclaimed: “‘“Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God.”’” Christ acted only on a “Thus says the Lord,” which remained the foundation of His ministry till the very end (John 12:49, 50). In Christ’s philosophical system, any mingling of human teaching with God’s Word is unacceptable (Matt. 15:9). In this way, Christ establishes the sola and tota Scriptura principles.

2. Christ’s work in the sanctuary is the ontological foundation. In John’s Gospel, Jesus revealed His being/name in relation to Exodus 3:14—the locus classicus of God’s being—where God revealed Himself as the Great I AM who works throughout spatiotemporal history to fulfill His covenant promises. He remembers His covenant spoken in the past to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (vss. 15, 16), hears Israel’s present cries for deliverance (vs. 16), and promises to deliver them, in the near future, from Egyptian bondage and carry them into a land flowing with milk and honey (vs. 17). In other words, by focusing on His past, present, and future actions, God indicated that He was a historical, relational, and missional Being. Just as the preincarnate Christ’s ontological self-revelation established the foundation of the sanctuary‑covenant structure, so do His seven Johannine “I am” statements serve to confirm His ontology in relation to the sanctuary:

a. I am the Bread (Ex. 6:22; the bread of His presence);

b. I am the Light (8:12; the seven‑branched lampstand);

c. I am the Door/Gate (10:7; the entrance to the sanctuary court);

d. I am the Good Shepherd (10:11; the priests of Israel as its shepherds);

e. I am the Resurrection (22:5; the resurrection as symbolized by the laver);

f. I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life (14:6; God’s way is in the sanctuary; Ps. 77:13; 73:17);

g. I am the True Vine (Christ’s life‑giving death on the sanctuary altar).

So, God reveals His being (ontology) as intrinsically connected to His actions in salvation history as articulated by the sanctuary‑covenant structure.

3. Christ’s metaphysics (principle of articulation) center on the prophetic nature of sanctuary typology. Even though Christ’s disciples had walked with Him for more than three years, they still had not understood His philosophical system of theology centered on the sanctuary covenant. It was not until after Christ’s resurrection that the light began to dawn. To the two disciples on the road to Emmaus, Jesus exclaimed: “‘O foolish ones, and slow of heart to believe in all that the prophets have spoken! Ought not the Christ to have suffered these things and to enter into His glory?’ And beginning at Moses and all the Prophets, He expounded to them in all the Scriptures the things concerning Himself” (Luke 24:25–27). Jesus gave Cleopas and the other disciple on the road that day a deep macro‑hermeneutical study centered on Old Testament prophecies. A while later, Jesus appeared to the eleven disciples and said: “‘These are the words which I spoke to you while I was still with you, that all things must be fulfilled which were written in the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms concerning Me.’ And He opened their understanding, that they might comprehend the Scriptures” (vss. 44, 45). Here, Jesus drew from the totality of Scripture, joining separate facts together into a comprehensive and coherent interlocking whole, to help the blinded disciples see what the Scriptures had been saying all along.

It would have been thrilling to have been there for that Bible study! Christ may have begun with the prophecy of Genesis 3:15, then, moving to the covenant with Abraham, He probably spent a good deal of time on the Exodus sanctuary‑covenant structure recorded by Moses, and then connected all that with the prophecies in the Psalms, Isaiah, and Daniel that pointed to His incarnation, sacrificial life, death, resurrection, ascension, and ensuing heavenly ministry. Soon after this class in intensive prophecy, Christ ascended to heaven; and the disciples, now better understanding the systematic plan of salvation, were boldly obedient to the faith. They understood that Christ was the sacrificial Lamb to whom the daily sacrifices pointed, they likely now also understood the 70‑week prophecy of Daniel 9, and were beginning to put together how all things in Scripture centered on Christ’s role as articulated by the sanctuary covenant. Similarly, “the sanctuary was the key which unlocked the mystery of the disappointment of 1844, [which] opened to view a complete system of truth, connected and harmonious.”6 So, the disappointment of the disciples after Christ’s crucifixion was lifted when He revealed the harmonious philosophical system articulated by the Old Testament sanctuary‑covenant structure that had, all along, pointed to His death, resurrection, ascension, intercession, and final judgment. Thus, the heavenly sanctuary began to emerge as the new center of spirituality in which Christ’s disciples were to follow Him by faith (Heb. 8:1, 2, 9:23–28, 11:13).

In summary, Christ’s philosophical system includes (1) Scripture as the epistemological foundation, (2) Christ’s sanctuary role as ontological ground, and (3) Bible prophecy and sanctuary typology as the metaphysical center.

Worldly vs. Biblical Philosophy: Paul’s Summary

Because no biblical writer was as philosophical as Paul, it is helpful to conclude with a brief analysis of his teaching on biblical philosophy and its relation to spirituality. In 1 Corinthians 2:6, 16, Paul presented two categories of wisdom/philosophy: (1) worldly and (2) godly:

“We do, however, speak a message of wisdom among the mature, but not the wisdom of this age or of the rulers of this age, who are coming to nothing. No, we declare God’s wisdom, a mystery that has been hidden and that God destined for our glory before time began. . . . What we have received is not the spirit of the world, but the Spirit who is from God, so that we may understand what God has freely given us. This is what we speak, not in words taught us by human wisdom but in words taught by the Spirit, explaining spiritual realities with Spirit-taught words. person without the Spirit does not accept the things that come from the Spirit of God but considers them foolishness, and cannot understand them because they are discerned only through the Spirit. The person with the Spirit makes judgments about all things, but such a person is not subject to merely human judgments, for, “Who has known the mind of the Lord so as to instruct him?’ But we have the mind of Christ” (NIV, italics supplied).

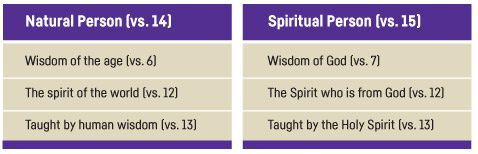

This text presents certain concepts equated and then contrasted with their opposites (see table below). The “wisdom of God” is identified with “the Spirit who is from God,” which “the Holy Spirit teaches.” These are contrasted with the “wisdom of the age” or “human wisdom,” which is identified with “the spirit of the world,” that is also the wisdom or philosophy taught by the rulers of this age. Paul designates as spiritual as the one having the mind of Christ through the teaching of the Holy Spirit (vs. 15), but the one who is led by the wisdom/spirit of the age he calls natural (vs. 12).

Figure 2

Both persons may be said to be spiritual in that they possess a spirit of wisdom, or a philosophy. The difference lies in what is informing their spirituality: is it (1) the Spirit of God through biblical revelation, or (2) the spirit of the age through worldly philosophy and culture?

It is important to note here that according to Scripture all humans are spiritual in that they all must—consciously or not—abide by some kind of coherent system of thought, some kind of wisdom/sophia. This goes back to the philosophical (macro‑hermeneutical) presuppositions that were explained above. Paul explains that sofia/philosophy can be biblical or worldly, but only the philosophy that is biblical, pure, and rational is acceptable for salvation.

Peter likewise affirmed this when he told believers to “gird up the loins of your mind” (1 Peter 1:13). “Girding the loins” meant to tuck the long flowing robe into the belt to get ready for work. This action, which always preceded hard work, Peter applied to the mind, essentially telling believers they needed to get ready to think deeply and critically. He then proceeded to speak about the enduring word of God (1:23–25) and charged his readers to “desire the pure milk of the word, that you may grow thereby.” Thus, in order to be saved, there must be continual mental growth in the understanding of Christ’s philosophy. But this must be a pure and rational understanding, untainted by the philosophy of the world.

In 2 Corinthians 10:5, Paul counseled believers to cast down “arguments and every high thing that exalts itself against the knowledge of God, bringing every thought into captivity to the obedience of Christ.” Casting down arguments could be a way to view the deconstructive effort of discovering whether the macro‑hermeneutical foundations of other theologies of spirituality align with those of Christ as conveyed in the biblical record.

Conclusion

This article has explored the history of spirituality in the early Christian Church, noting that the apostles warned believers to not be conformed to the world, but to be transformed into the image of God through the renewing of the mind. Even at that early date, Paul had detected a mystical spirituality infiltrating the church that bypassed all rational thinking based on God’s law and instead sought the immediate presence of God. Paul also helps us see that while all humans are spiritual, everyone is guided by one of two spirits/philosophies: either the philosophy of the world, or God’s philosophy as revealed through His Holy Spirit to the prophets. And this revelation of God’s mysteries was written down so we might develop a vibrant personal relationship with our God and grow daily in our spiritual union with Him.

Silvia Canale Bacchiocchi, MA, is studying for a PhD at the Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary at Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan, U.S.A.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

1. Philip Sheldrake, Spirituality: A Guide for the Perplexed (New York: Bloomsbury, 2014), 5.

2. Unless otherwise noted, all Scripture references in this article are quoted from the New King James Version of the Bible.

3. Oxford English Dictionary, C. Soanes and A. Stevenson, eds. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

4. F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone, eds. “Mysticism, Mystical Theology,” Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 1,134.

5. Pseudo-Dionysius, “Mystical Theology” in Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 137.

6. The Great Controversy, 423.

1. Philip Sheldrake, Spirituality: A Guide for the Perplexed (New York: Bloomsbury, 2014), 5.

2. Unless otherwise noted, all Scripture references in this article are quoted from the New King James Version of the Bible.

3. Oxford English Dictionary, C. Soanes and A. Stevenson, eds. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

4. F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone, eds. “Mysticism, Mystical Theology,” Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 1,134.

5. Pseudo-Dionysius, “Mystical Theology” in Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 137.

6. The Great Controversy, 423.